Ableism — prejudice against people with disabilities — is rooted in disability myths and historical stigmas, some of which date back hundreds or thousands of years. Systemic ableism perpetuates those biases in such a way that people tend to internalize them and accept them as the truth.

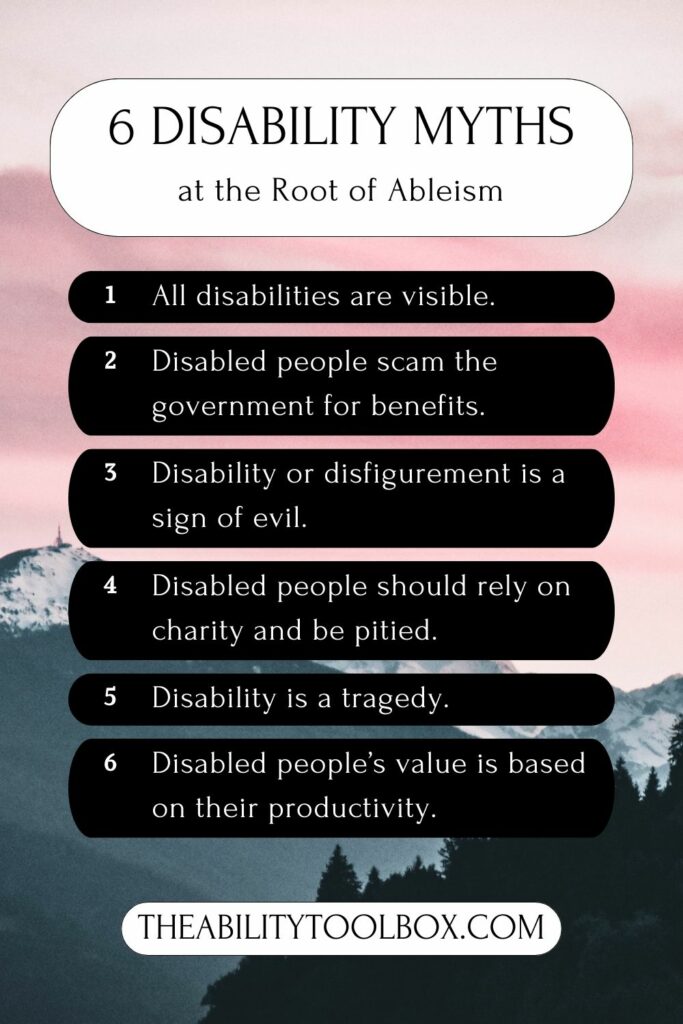

Let's bust six ancient disability myths that are still pervasive in individual attitudes, government programs, educational entities, and businesses.

Myth: All major disabilities and chronic illnesses are visible.

This is one of the most damaging disability myths permeating society today. Not all disabilities are visible. In fact, most disabilities are invisible.

Many disabilities cause chronic fatigue, pain, and other debilitating symptoms but do not affect a person's ability to walk short distances. And of course, mental illnesses and neurodivergent conditions such as autism and ADHD usually do not change a person's appearance.

Due to this myth, people with invisible disabilities frequently struggle to find doctors who will treat them with understanding and help them get the medical care and support they need. They are subjected to gaslighting comments such as “You don't look sick” and routinely denied reasonable accommodations at school and work because non-disabled people refuse to believe they really need them.

People with invisible conditions have developed the spoon theory to help non-disabled people understand their experiences. If you've ever questioned whether someone is disabled because they look able-bodied, you should go read about it now.

Myth: People with disabilities scam the government for free money.

People with disabilities are often falsely accused of faking their conditions and scamming the government for benefits, especially if they have an invisible disability or mental illness. Due to this disability myth, it is extremely difficult for people with invisible conditions to qualify for programs like SSI and SSDI.

Despite the prevailing myth of rugged American individualism, we all need and rely on government services. However, people are judged for needing certain services, but not others. Ableism is the reason why people are regarded as undeserving if they receive SSI but not if they receive farm subsidies or child tax credits.

Myth: Disability is an outward manifestation of evil, sin, or personality flaws.

In ancient times, people with visible disabilities, or who developed then-common diseases like leprosy, were often considered to be cursed. A disabled child was punishment for a family's sins. People with mental illnesses were believed to be possessed by evil spirits or the devil.

If you think we have fully evolved beyond these damaging disability myths, consider how frequently the villain in movies has some kind of disability or disfigurement, and how people with mental illnesses like schizophrenia are still wrongly assumed to be dangerous and “possessed.”

Myth: Disabled people should be pitied and cared for by charitable organizations.

This is the opposite of the “disability is a sign of evil” myth, but both exist simultaneously in American culture. The tragedy stereotype depicts disabled people as helpless, pitiable victims who need to be saved by able-bodied people. This performative “charity” enables non-disabled people to feel good about themselves and reinforce their own status as superior to those they are “helping.” People with disabilities are just the recipients and have no power or agency in their own lives. They are expected to be grateful for any crumbs thrown their way, and labeled demanding and entitled if they assert their rights or explain why what is being offered won't help them.

The old Jerry Lewis Labor Day MDA telethons were a prime example of how disability charities operated in past generations. When people with muscular dystrophy started criticizing Jerry Lewis for how they were being portrayed on national TV, rather than listening to the community he supposedly wanted to help, he made numerous offensive and deeply ableist comments. Non-disabled people were shocked, but most disabled people were not, because it was obvious that he had been exploiting them to feed his own ego.

Myth: Disability is a tragedy.

Disability is a state of being. It's not inherently good or bad — it just is. We attach judgments to it based on many factors, some of which have much more to do with stereotypes and assumptions than whether a disability is bad in and of itself. This stereotyping leads to discrimination that is often more harmful than any symptoms a person may experience. For example, if a blind person keeps getting rejected for jobs after the interviews despite being well-qualified, their blindness is not the issue. Likewise, many Deaf people don't consider their deafness to be a problem, except that hearing society discriminates against them.

Yes, some people are disabled by extremely debilitating or terminal illnesses. Disability can be limiting and it can be difficult. However, treating disability as a tragedy does not help. When you pity people with disabilities, you’re treating them as less than. Feeling sorry for someone never helps them. Treating disabled people with respect is part of the solution, but it must be backed up by your actions, such as supporting robust services for all and financial supports for those whose disabilities make them unable to work.

Myth: A person's value is based on their productivity and how much they can contribute to capitalism.

This is, arguably, the root of all ableism. In a capitalist society, humans are valued based on how much money they can earn and how much work they can do. Since some people with disabilities cannot work (or cannot work “enough” doing the “right” kinds of labor), they are seen as inferior, and regarded as drains on the system rather than contributors.

Society's demand that humans meet a narrow definition of productivity underpins many ableist myths and toxic tropes. Here are a few examples:

“The only disability in life is a bad attitude.”

This one is the worst! In truth, often other people's bad attitudes are disabling, and so is systemic ableism. To quote the late, great Stella Young, “No amount of smiling at a flight of stairs has ever made it turn it into a ramp.”

People with disabilities also often get labeled as having bad attitudes when we have the audacity to confront ableism and demand our rights. How dare we!

“Disability can be overcome if you try hard enough.”

If only! “Trying hard” won't cure any disability, nor will it magically erase systemic ableism. Of course, we should all do our best to make a good life for ourselves with the cards we've been dealt, but you can be a Senator and the airlines will still break your wheelchair.

The system is set up for disabled people to fail. Those who managed to succeed despite it should be applauded, but those who continue to struggle despite their best efforts are not at fault.

Busting Disability Myths in Your Everyday Life

In my experience, the best way to bust disability myths is to be yourself. Sure, a snappy comeback to an ableist comment can be fun when the timing is right, but if you're shy or don't know what to say in the moment, that's OK. Just get out there and don't let other people's ignorance stop you from living your life.

Yes, it's incredibly frustrating that we are in the 21st century and still dealing with disability myths from hundreds of years ago. But then again, society is also still dealing with racism, sexism, homophobia, and other outdated views, so it's really not that surprising. And things are getting better, slowly but surely.

In just 30 years, the ADA has made the United States vastly more accessible. We're finally seeing more actors with disabilities in TV and movies. Technology has created more opportunities for disabled people to work and connect with one another. Our increased visibility in society is busting disability myths one by one and showing how much we can accomplish.

What other disability myths have you encountered?

Share your experiences with our community in the comments.

Founder and Editor-in-Chief of The Ability Toolbox. I received my BA in English from Stanford University and MA in Clinical Psychology from Antioch University Los Angeles, and have worked in entertainment and health media for over 20 years. I also blog about traveling with a disability. As a wheelchair user with cerebral palsy, I am deeply committed to amplifying the voices of the disability community through writing and advocacy.

Start the discussion at community.theabilitytoolbox.com