Often conflated with dissociative identity disorder, bipolar disorder (BD), or manic depression, is one of the most widely misunderstood and wrongly portrayed mental disorders in popular media. As a writer who has struggled with bipolar disorder for years and has featured it prominently in his work in one way or another, it’s not only frustrating to see so little representation of a disorder common among artists, but to have it be as misrepresented as it is when decades have been spent educating the public on it.

Of course, there is no one right way to present the disorder in your work, but over the years, it’s become clear that there are plenty of wrong ones. For some reason, the increased respect and care in the way we treat those with mental health disorders have not yet extended to the way the media portrays them, with the same tired, troubling tropes cropping up whenever a character who’s meant to have bipolar disorder shows up. But, with the right kind of research and preparation, this can be amended, and one day, the cycles of misinformation and misrepresentation can hopefully be broken.

Bipolar Disorder Media Misconception #1: “The Mood Swinger”

Even when writers think they’re familiar with the general strokes of the condition, their portrayal of characters with bipolar disorder has led to the creation of the “mood swinger,” a fanciful archetype that general audiences have come to associate with the disorder. This is frustrating, and not just for those with bipolar disorder, because the archetype is actually an amalgamation of symptoms from various other disorders packaged with stock “quirky” tropes to make it palatable or have their characters come off as “eccentric” geniuses.

Mood swings are a symptom of multiple mental disorders, but the predominant portrayal of characters with bipolar disorder is to make them a mood swinger, i.e., a character who is defined by a propensity to drastically alternate moods in a short span of time. That may seem to align with ultradian-cycling bipolar disorder, where mood swings can occur in a matter of hours. But, not only are mood swingers an inaccurate portrayal of bipolar disorder since even ultradian-cycling takes hours (not minutes or seconds as is the case with mood swingers in popular media), ultradian-cycling is comparatively much rarer, so having it that be the predominant portrayal of bipolar disorder misrepresents the common form of the disorder to the public.

What separates bipolar disorder from other disorders characterized by mood swings is that the moods tend to not only be prolonged periods but distinct from the patient's usual behavior. No outer stimuli trigger it, and the mood is either manic (i.e., euphoric, energetic, and prone to irritation) or depressed (i.e., low accompanied by nervousness or lack of energy) with states along a metaphoric axis of differing intensities. These bouts are spontaneous, reoccurring throughout the year, changing you completely as a person and severely impeding your functions. That nuance is hard to capture in fiction, but having time pass between shifts in mood is important to depicting bipolar disorder accurately.

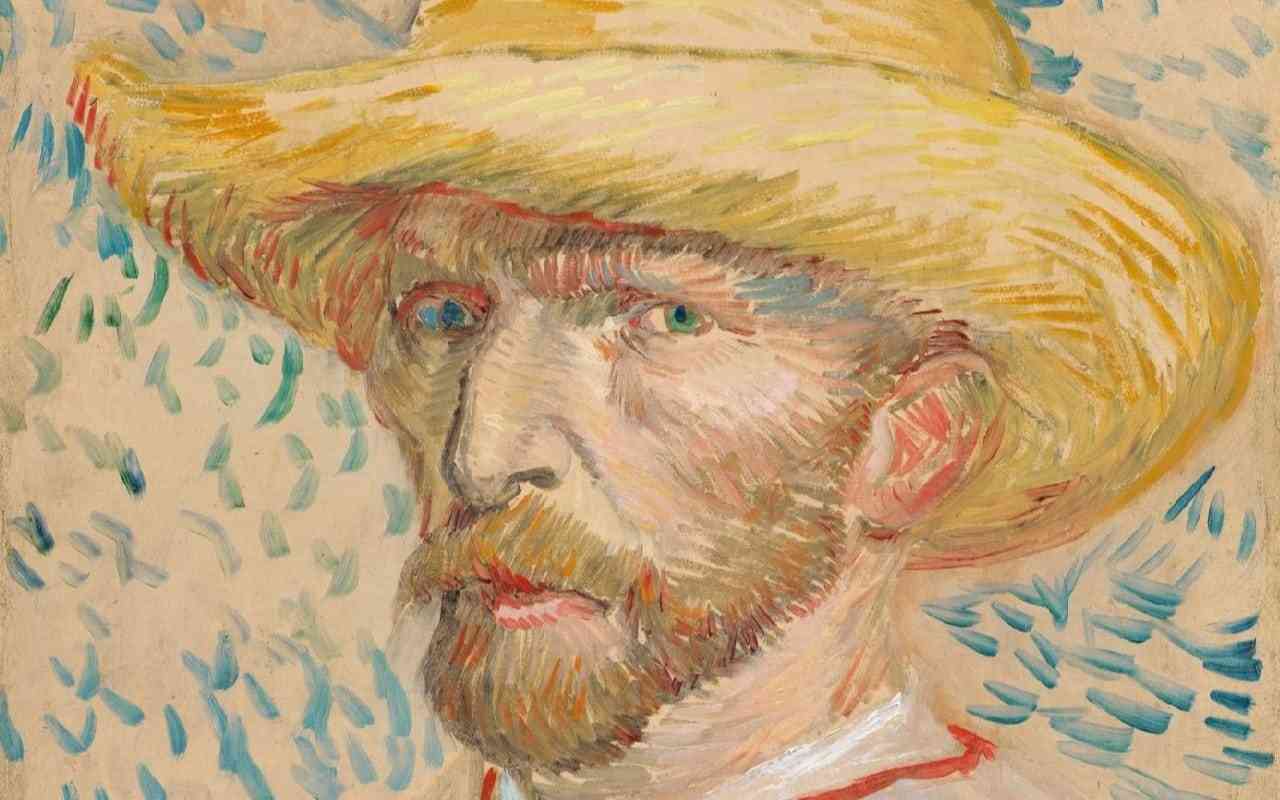

Vincent van Gogh was widely theorized to have had bipolar disorder, but you wouldn’t know it from his portrayal in “Vincent and the Doctor,” an episode from season 31 of Doctor Who. All the hallmarks of the moods swinger are present in this depiction, with Vincent cycling from functional to inconsolable to battle-ready within minutes when in real life, the process occurred over periods of weeks or months.

Bipolar Disorder Media Myth #2: Treating It as Edutainment

Now, even though portraying bipolar disorder properly is important, not every work featuring a character with the condition has to be a documentary or lecture on the subject. Of course, there are great examples of media like this (Ellen Forney's Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me: A Graphic Memoir comes to mind), but having all media that features bipolar disorder like this would be problematic. People with bipolar disorder, and mental illnesses, in general, aren’t walking, talking edutainment services trying to explain the minutiae of what they’re going through to uninformed audiences, and media depicting them shouldn’t be either.

Furthermore, if a work features a character with bipolar disorder, it doesn’t need to be about it at all. In Michael Clayton, one of the major supporting characters, played by Tom Wilkinson, has bipolar disorder, and it is a plot point, but the movie doesn’t spend time explaining what it is to the audience, only treating it with the gravity that the situation in question deserves. I’d go one step further and say that it doesn’t need to factor into the plot in any way. After all, my condition is not a Chekov's gun that’ll fit neatly into a three-act structure.

Bipolar Disorder Misrepresentation #3: Characters' Lives Should Revolve Around Their Illness

Just like bipolar disorder doesn’t need to be the entire focus of the work, a character’s existence shouldn’t revolve around it either. Bipolar disorder shouldn’t define a character the way bipolar disorder doesn’t define my life. I’m more than the disorder, and if all the audience can think of when they think of your character is that they’re bipolar, then you need to think of ways to expand on their character and add depth and layers to them. Even though bipolar disorder is defined by distinct moods, those moods never manifest in the same way each time and manifest differently in different people. The personalities of people with bipolar disorder are not homogenized when experiencing one of these moods. Rather, their distinct personalities are altered by it, so even if the character with bipolar disorder is only shown in one of their moods, their distinct character can be revealed through it.

In Steven Soderbergh’s The Informant!, the protagonist, Mark Whitacre, has bipolar disorder, but the movie focuses on his time as a whistleblower, and bipolar disorder doesn’t define (nor is it treated as the reason for) his distinct, off-color personality.

Bipolar Disorder Media Truth #1: We Can Laugh About It

When bipolar disorder is properly portrayed, it’s rare to find humor in the writing, but I would argue against that. Bipolar disorder is no laughing matter, but living with it is not all doom and gloom, and I’m always cracking jokes about it at my expense. Not everyone with bipolar disorder is comfortable with that. But, having the subject be treated like a death sentence can make it feel like I’m being victimized when I would personally rather not treat it (or have others around me treat it) with that kind of solemnity. That doesn’t mean, however, that there’s no fine line between tasteful humor made in good faith and writing that’s outright disrespectful and bigoted.

Carrie Fisher’s memoir Wishful Drinking walks that line, leaning into her trademark sardonic humor, and shows what life would bipolar disorder is like without making it come off like it’s a neverending nightmare. Though it may seem crass, Fisher is careful with her words and takes the time to unpack what she’s joking about it and how it’s one way for her to cope with it.

Bipolar Disorder Media Truth #2: You Can Lead a Great Life

Fisher, like many others with bipolar disorder, was able to lead a great life with more success than most of us could hope to amass in many lifetimes. I think showing that people can lead great lives with bipolar disorder can inspire others living with mental illnesses. Silver Linings Playbook does a great job of showing that even with hurdles along the way, you can find happiness and fulfillment. The film isn’t afraid to take its protagonists to dark places, never sugarcoating the experience and taking care to explain, but not justify, when things take a turn for the worse.

The Importance of Mental Health Sensitivity Readers

Everyone’s response to the portrayal of bipolar disorder will vary, and it’s always best to err on the side of caution. Having sensitivity readers go through what’s been written and offer their takes on it is a must, in my opinion. Doubly so if you haven’t been diagnosed with it, as research alone has proven time and again not to be enough, and you’re always at risk of doing more harm than good by misrepresenting BD and what it’s like to live with it.

Many examples from popular media claim to have spent the time to research the subject matter, only to end up with a mood swinger on a perpetually downward spiral. Richard Curtis, the writer behind the aforementioned “Vincent and the Doctor,” was vocal about his fascination with the life of Vincent van Gogh. Well-acquainted with the subject, he claimed he put in more time into the research than he usually would’ve and read a 200-page biography on the man. Though Curtis took the writing of the episode seriously, and his depiction of depression was lauded, the way he portrayed van Gogh still made him a mood swinger when that wasn’t the case in real life. Not to mention, it added some problematic touches, like linking his condition with a superpower — which would take a whole other article to dissect and condemn.

In the end, though this article might seem like it’s trying to limit what can be done with characters with bipolar disorder, I think of it as a launching pad for a whole new creative approach to portraying it. Tackling bipolar disorder with care and nuance has yet to become the norm, and if we are ever to normalize the condition in the eyes of the public, the way we portray people who live with it has to change.